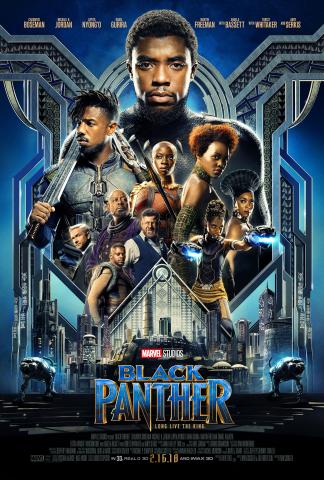

A couple of weeks after the great hype had toned down, I finally went to see Black Panther. Intrigued as I was about the grand way in which the movie was hailed as some sort of liberation theology for black people, I refused to read any reviews and let the movie speak for itself. Could it really live up to the proposed breach of ‘Hollywood whiteness’? Was it truly such a “dope-ass black movie” as anti-racist television personality Trevor Noah made it seem to be in his Daily Show? Or was it yet another bizarre twist of consumer culture that lured people into thinking this was a norm changing movie even though it actually offered an overdose of those norms?

As it turned out, the latter was the case. With every minute of movie, my sense of disbelief became greater and finally ended in the certainty that this was a nationalist, xenophobic, colonial and racist movie.

Surfing around on the net afterwards, I quickly realized I wasn’t alone. For example, an article by Kenian political cartoonist Patrick Gathara on the website of the Washington Post, offered some very relevant, thorough arguments. It described how “at heart, it is a movie about a divided, tribalized continent, discovered by a white man who wants nothing more than to take its mineral resources, a continent run by a wealthy, power-hungry, feuding and feudalist elite, where a nation with the most advanced tech and weapons in the world nonetheless has no thinkers to develop systems of transitioning rulership that do not involve lethal combat or coup d’etat.”

Gathara goes on to explain how Black Panther, with a typical Victorian slant, portrays Africans as primitive yet in harmony with nature, not faced by the complexities of modernity; how the Wakandans technological advancement, apparently still doesn’t make them sophisticated enough to prevent a single American from overtaking the country; and how it thus eventually tells a neocolonial story about somewhat childish people who need a strong guiding hand to lead them.

As Kif Kif predominantly publishes Dutch articles,

our English articles can also be read on our English only Medium magazine.

As such, it’s painful to see how blinding a shiny neoliberal story about ‘triumphing blackness’ can be. Give people some feel-good popcorn and any critical analysis, seems to be thrown into the trashcan faster than anyone can even gobble up the Kool-Aid. So, to strengthen the case of an alternative view, I simply would like to add the following list of 15 reasons why Black Panther is rather problematic.

First, the obvious things…

1. The bluntly racist images: Not only does the movie end with African tribes fighting each other with spears, clubs and machetes but the men of the ‘strong tribe’ in Wakanda dress like monkeys and literally make oo-oo-oo sounds. Sure, the latter might perhaps be part of the original comics as well, but that doesn’t imply one is obliged to transfer the exact same imagery to the movie. If someone were to make a movie of Tintin in Africa and used the same old imagery ‘because the comic portrayed Africans in that way’, we’d all take offence and rightfully so because the images from that comic book are now considered to be racist. In a very similar manner the portrayal of M’Baku in the original Black Panther comics has also been problematic from the start.

2. The duality of ‘good blacks’ vs. ‘bad blacks’: The good guys are authentic, pristine Africans, who still live in harmony with nature. The bad guy is your typical ‘black boy from the hood’. As such, tapping deep into the typical colonial imagery of the ‘unspoiled primitive’ the ‘good’ black is the romanticized and completely idealized black. The ‘bad black’, on the other hand, is simply the contemporary and ‘real life’ black American.

3. The comparisons with the Lion King: The narrative similarities with the Lion King are painfully obvious: the king of the pristine and glorious land, is betrayed by his Uncle/Nephew, after which the new king is banished, yet he returns and with the help of his lioness(es) and warrior monkey(s), he’s saved. It only lacked a remix of the song The Circle of Life to make the message complete: Africa = savanna.

4. The crude portrayal of voodoo and its importance for the story: What makes Black Panther so strong is not his skill or his brains. (In fact, when ‘simply human’ he loses the fight quite often.) Rather, what makes him strong is some sort of voodoo trick involving plants, shamanism and a drug which makes your veins literally black as if you’re possessed by a Demon — which eventually the Black Panther is, since you can just as well ‘exorcise’ him with some counter-voodoo. And of course, the viewer won’t find any references to deeper philosophy, mythology or theology of genuine Ifá. No, the viewer only gets to see the crudest archetypical Hollywood portrayal of voodoo-as-black-magic.

Then, the somewhat more hidden stuff

5. The strange message of the futuristic element: There is no need to attack the genuine cultural phenomenon of afrofuturism at large, but what I found at least a bit bizarre from the start of the Black Panther hype was the craze for the fact that finally there was a movie about blacks who were technologically advanced. When the whole movie is about a mysterious country that pretends to be poor and outwardly projects a typical image of a third world country while underneath its surface lies some incredibly advanced technology, the eventual message simply seems to be this: “See, underneath every seemingly primitive African hides a (possible) modern Westerner!”

6. The contrasting morality of blacks and whites: All black protagonists are morally ambivalent. King T’Chaka, is a good king and father but hides his mistake, general Okoye is very loyal but because of her loyalty goes through a conflict of conscience when Killmonger takes over, the border guard W’Kabi is strong and adamant, but eventually chooses to follow Killmonger when the latter comes to power, king T’Challa has a good and wise heart but has many doubts throughout the movie. Even N’Jobu, who betrayed king T’Chaka, only did so because he was genuinely aggrieved by the plight of African Americans. The same is true for his son: he’s power hungry and aggressive yet also hides a deep love for his father and upholds a sincere wish to free ‘his people’. The only non-ambivalent characters are the two whites. Ulysses is pure evil and Everett is pure goodness. Concerning the latter, even though he’s a CIA agent, his motives are never questioned, his past is irrelevant and his dominant personality trait is one of ‘cute naive innocence’. He not only selflessly saves a life half way through the movie, but in the end also saves the world (since he stops the war planes from reaching their destination).

The only non-ambivalent characters are the two whites.

7. The seemingly subversive but eventually not so impressive flips of gender roles: In Wakanda, women are seemingly strong. But eventually there’s no question whatsoever that the men are the kings and the women (even when they’re fierce warriors or genius scientific whizz-kids) are on a constant lookout for a man who can help them. As such, general Okoye still needs the guidance of a righteous leader and princess Shuri needs someone to fly her plane. The only ones taking matters truly into their own hands (i.e. without following orders or loyalties) are men.

8. The role of vibranium (and how it’s the only thing that makes Wakanda ‘advanced’): When Wakanda is an advanced technological country, it’s not because of their inherent intelligence or their approach to society. It’s a ‘coincidence’ and has everything to do with a special resource: vibranium. (It’s also taken for granted they do not wish to share this resource with the rest of the world and that as such it will not only lead to technological advancement but also to conflict.)

9. The convoluted relation between tradition and power: In Wakanda, the traditions of old are seemingly revered as holy. But when the King loses in a fair fight, all of the sudden, anything goes. He can breach traditions and retake his power simply because he’s ‘the good guy’. So eventually there is no sanctity of tradition at all. It’s simply about power. The colonial undertone should be clear: ‘Africans are stuck in their traditions. They should abandon them, because power is what truly makes the world go round.’ This becomes amply clear in T’Challa’s relation with Killmonger. One of T’Challa’s great grievances is the fact that his father left a Wakandan kid behind in ‘the hood’ and did not try to save him from his lot (which, of course, could apparently do nothing but make him aggressive). Yet killing that same kid simply because he’s not likeable when he’s a bit older is seemingly OK — even though Killmonger won the traditional battle fair and square. Though morally completely inconsistent, it does remain very consistent with the already mentioned dichotomy of the ‘good’ (pristine African) blacks and ‘bad’ (hoody) blacks. And of course, the ‘bad’ blacks by definition want to take over the world because they hate whites — so they have to be stopped, no matter what tradition or morality dictates.

The colonial undertone should be clear: ‘Africans are stuck in their traditions. They should abandon them, because power is what truly makes the world go round.’

10. The dominance of the underlying myth of the hero: The most classical structure of probably 99% of all blockbuster Hollywood movies is the classical ‘myth of the hero’. The hero who first felt small but received support from a wise man; the hero who travels and conquers dangers; the hero who confronts his darkest fears in an epic battle for evil; the hero who not only saves himself but also the world. Although it’s a universal story, in modern Western culture it’s so dominant that it seemingly became the only way to tell an exciting story. Just compare, for example, Disney hits with, for example, some Japanese anime hits from studio Gibli. The latter are full of more Buddhist themes and as such often stray from the typical myth of the hero pattern. In various African cultures as well, other mythical patterns and archetypes can be found in the traditional storytelling. However, Black Panther is, from start to finish, the purest form of the hero myth. Even the previous Avenger movies such as The Winter Soldier and Civil War breached the pattern more (having the superheroes fighting each other). Yet in Black Panther there’s no single cultural change or breach of this subconscious hero pattern. As a result, there’s also no trace whatsoever of philosophical concepts like Ubuntu or the morality underlying the well-known South-African truth-commissions. There is only one simple plot: a dualism of good vs. evil and a hero who saves the day because he fights bravely and eventually crushes evil in an antagonistic fight.

11. The Westernization of Wakanda as a result of the hero myth: Eventually the journey of the hero leads to Wakanda becoming a ‘modern state’ like Western states. After the fights have been settled and all is said and done, Wakanda becomes more open (read: less protectionist and thus more neoliberal). It also portrays a tendency to go and ‘save others’ through outreach programs. All in all then, the whole ‘technological advancement’ of Wakanda was nothing but a shallow layer. Eventually the story is still about a ‘not so modern’ country that needs to be ‘modernized’ by a King more in contact with the West.

And finally, the most disconcerting xenophobic and nationalist issues

12. The supremacy of nationalism: Just like any other successful blockbuster, the cinematic tension isn’t simply built on the action and special effects, but also on a couple of moral dilemmas which define the relationships between the protagonists and ignite the dynamics of the story. The first moral dilemma in Black Panther, which surfaces in various forms, is between love for a person and love for a nation. One example is how T’Challa and Nakia apparently can’t marry because of T’Challa’s loyalty to his kingdom and Nakia’s wish to help those outside the country. They only find a solution in T’Challa giving state subsidies to Nakia’s work. A second and even more explicit example is played out between Okoye and W’Kabi. Which of the two types of love should be held high is made most obvious when they confront each other in battle: “You would kill me my love?” W’Kabi asks. Okoye unflinchingly answers: “For Wakanda? Without question.” Hence, nationalism is the main ideology of Wakandans. The nation state is supreme and should receive the highest love of its citizens. Even though the concept of nation states is a product of modern, Western culture, the question is never asked what a traditional Wakandan view of society might be. Nationalist ideals are taken for granted and they’re only threatened when Wakandans fall in love or when they ‘relapse’ into tribalism.

13. The antagonism of state and race: The second moral dilemma which surfaces throughout the movie is between ‘loyalty to the state’ and ‘being the leader of ‘the cause’ — the cause being ‘the effort to save other blacks’. In short: a dilemma between state and race. Apparently Wakanda doesn’t have any other cultural or traditional approach to these matters. The elite of the country hold very similar ideas as white nationalist elites which have a long history of societal dilemmas between ‘protecting their country’ and ‘protecting mankind from barbarians/primitive races/terrorists/…’

The nation state is supreme and should receive the highest love of its citizens. Even though the concept of nation states is a product of modern, Western culture, the question is never asked what a traditional Wakandan view of society might be. Nationalist ideals are taken for granted and they’re only threatened when Wakandans fall in love or when they ‘relapse’ into tribalism.

14. The projection of typical white xenophobic fears: Following from the two previous moral dilemmas, the typical xenophobia of Western whites has been fully projected onto blacks. The Wakandan elites don’t want to open the borders of their country for refugees because they want to preserve the ‘purity’ of their pristine country and culture. It even instituted Frontex and USBP style border patrols. There actually aren’t many blockbuster movies where such a contemporary form of xenophobia (rampant in Europe and the US) is so explicitly, consistently and straightforwardly portrayed. Yet once it does take center stage and becomes a central part of the critique within an action movie aimed at a broad public, apparently it’s something black people are culpable of. (Also interesting in this respect: in all their fear to preserve their ‘pristine’ Wakandan nature and culture, apparently their technological advancements are of no concern whatsoever. For some magical reason, their technology simply doesn’t seem to have any impact on their nature or culture. I guess vibranium is by definition ‘clean vibranium’ — just like Tump’s mythical concept of ‘clean coal’.)

15. The blackwashed white savior complex: When a solution for the dilemmas of ‘personal relations’ vs. ‘state loyalty’ and ‘race’ vs. ‘state’ is eventually found, that solution exists in ‘outreach’. Why not truly open Wakanda, bring in all the refugees and show that another society is possible? Why not start sharing knowledge and technology with other African countries to make them economically stronger and thus break the true strength of the former colonialists and current neocolonialists? No, the only option is to act exactly like the (neo)colonizer: take pity with a group of downtrodden people in a faraway country, collect some money ‘for the poor’ and then missionize, patronize and civilize. As such, the outreach programs are also by definition oriented on blacks who are in need of help (the ‘bad blacks from the hood’ who need to be turned into ‘good blacks’), even though Wakanda could just as well start outreach programs among whites, for example, to decolonize their minds.

So, to conclude

Sure, representation in Hollywood matters. Sure, we need more black heroes. Sure, we need more strong female characters. But in the end, Black Panther is nothing but a racist, colonial, xenophobic movie. It’s a distinctly Western technology worshipping myth of the hero. It’s blackwashed white nationalism.

So now the hype has gone, perhaps it’s time for some thorough analysis and criticism. No, we shouldn’t applaud this type of movie because it has some cool black women warriors and a shiny afrofuturist Panther King. Quite the contrary, we should strongly resist such neoliberal efforts to commodify, commercialize and privatize the anti-racist struggle.